HARSHVARDHAN BHATKULY

Some teachers never stop their stints at the blackboard, and they go on to educate generations. Vasco Pinho, who passed away in the last week of December, belonged to that rare breed of scholars whose academic prowess lied in imparting classroom knowledge in the fields of commerce and economics; while his passion lay in educating generations on the history of the city of Panaji. He also remained the city’s lifelong student. His textbooks were the city’s streets, archives, churches, bairros and forgotten footnotes. To many, he was a meticulous historian; to some, a tireless chronicler.

Pinho’s literary contribution to the history of Panaji is remarkable not only for its depth but also for its intent. He did not write history to impress academia or chase citations. He wrote to preserve memory. At a time when Panaji was rapidly transforming – architecturally, socially and culturally – he sensed an urgent need to document what was slipping away. With no formal training in history, he relied instead on unrelenting curiosity, discipline and deep respect for sources. This self-taught approach gave his work a rare honesty and accessibility.

Pinho taught economics and commerce at St. Xavier’s College, Mapusa, shaping young minds in a formal academic setting even as he pursued historical research independently. That grounding in economics perhaps sharpened his understanding of urban systems, institutions and social change–elements that surface subtly but consistently in his historical writing.

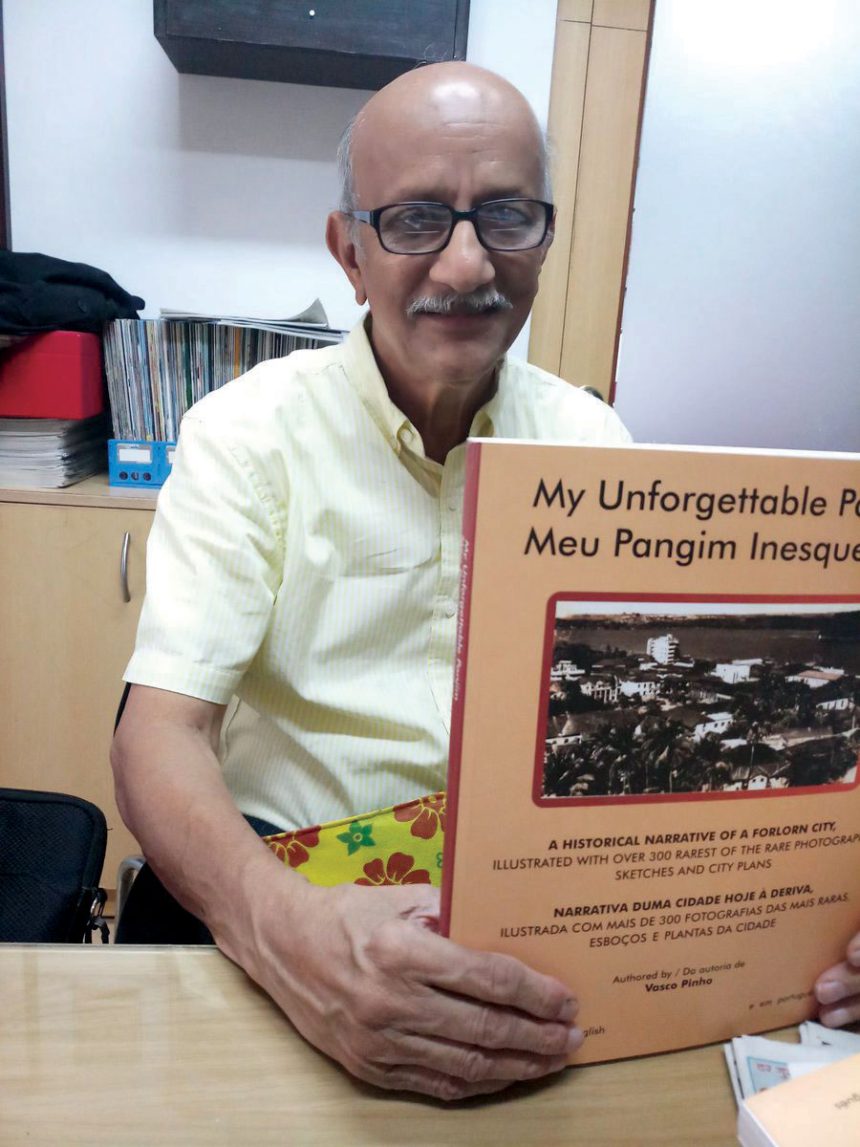

His ‘Snapshots of Indo-Portuguese History’ series, spread across four volumes, stands today as one of the most comprehensive narratives of Panaji and the colonial history of Goa. Two books in the series are dedicated to the city – layered with detail: the evolution of neighbourhoods, the influence of Portuguese administration, the role of institutions, the rhythms of everyday life, and the people–known and unknown – who shaped the city. There is also a stark pictorial ‘then and now’ documentation that could make one gape in wonder how much the city has changed. Pinho wrote with the patience of an archivist and the affection of a resident who belonged deeply to the place he was documenting.

What set his writing apart was his refusal to romanticise blindly. While he loved Panaji, he did not shy away from uncomfortable truths – social hierarchies, urban neglect, or historical contradictions. His Panaji was living, breathing and imperfect. In doing so, he rescued local history from nostalgia and gave it intellectual credibility rooted in primary research, oral histories and painstaking cross-verification.

He was also a keen student of the Portuguese language and his book to learn the language is a beginners’ delight. Pinho contributed regularly to The Navhind Times in the late 1990s. His collection of columns, which would take people of his generation back in time, was published as ‘Nostalgia’. Many readers would write back saying that his column would rekindle the life that they once enjoyed. With ‘Nostalgia’, Pinho wrote the experiences of a generation of Goans.

Away from books and archives, Pinho lived a life grounded in simplicity. Along with his wife Ruth, he ran a toy shop at Velho Filho in Panaji – an almost poetic counterpoint to his scholarly pursuits. That small store was more than a business; it reflected his gentle engagement with everyday life, children, families and the rhythms of the city he loved so deeply. Scholar, teacher, shopkeeper – these roles coexisted seamlessly, revealing a man who never believed knowledge had to be divorced from ordinary living. His pit stop, Café Tato, where he relished the famed ‘bhaaji-puri’, was just around the corner. He would also walk in the city garden, stopping often to chit-chat and exchange pleasantries with familiar faces.

Pinho never positioned himself as an authority. He was more comfortable calling himself a student of Panaji, even after decades of research. That attitude is perhaps his greatest legacy. He showed that one does not need institutional validation to contribute meaningfully to knowledge – only sincerity, patience and love for place.

As Panaji negotiates the pressures of change and modernity, his work stands as a quiet but firm reminder that cities are not just built spaces, but accumulated memories. His books do not merely tell Panaji’s story; they ask us to pause, to observe and to care. In remembering Panaji so faithfully, Pinho ensured that the city will continue to remember itself.

(The writer is is a lawyer

and media personality)