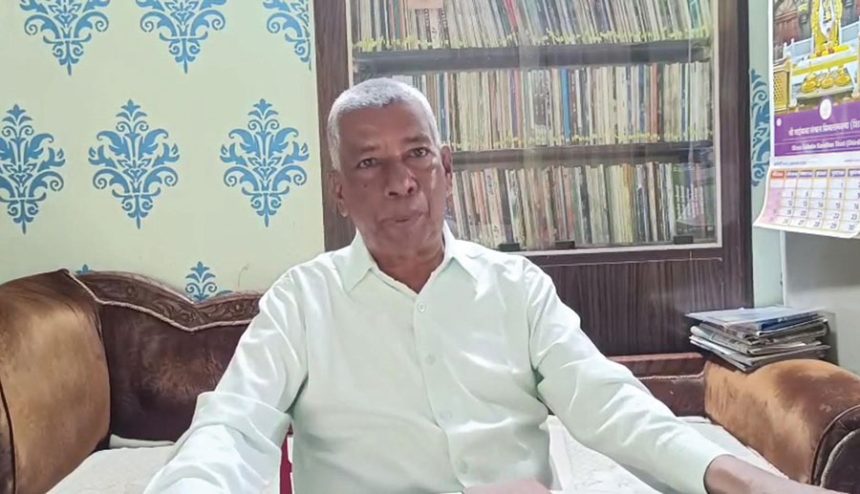

As Goa celebrates Opinion Poll Day, also known as Asmitai Dis, Abel Barretto of The Navhind Times revisits the historic 1967 referendum through the memories of Ramesh Komarpant. As a teenager, he not only witnessed the intense canvassing by pro- and anti-merger supporters, but also actively participated in the anti-merger movement that shaped Goa’s future

As someone who witnessed it firsthand, how did the Opinion Poll shape your own sense of Goan identity?

I was a young teenager of 15 years old then, a period in a youth’s life for understanding and practising social responsibility. Goa was active with a political struggle, with discussions everywhere about merging with Maharashtra or remaining a separate Union Territory. Meetings were held at Ponsamulank, under the jackfruit tree at Chaudi, a central part of Canacona, by people advocating both opinions — for the Maharashtra merger and for a separate territory. Though I studied in a Marathi-medium school, my love for my mother tongue triumphed, and I strongly supported the Konkani language movement in the state.

What do you remember most vividly about the atmosphere in Goa leading up to the Opinion Poll?

During the Opinion Poll period, discussions would take place at designated places. The public would attend meetings of both the ‘for’ and ‘against’ sides. It was a self-awakening experience, as very good speakers and singers from Maharashtra would come to present their views and opinions. Bab Uday Bhembre’s talks during the Opinion Poll struggle impressed me and had a great impact on me. No money or other influences could change anyone’s opinion in those days. Though a section of some persons blindly followed political leaders, the thoughts of most Goans were self-analytical and introspective during the Opinion Poll. The slogan ‘Nakothishrikhandpuri, amchixittkodibori’ was chanted all over Goa, and it still echoes in my mind today.

Looking back, what do you think Goa would have been like if the result had gone the other way?

During gatherings, when we discuss the impact of a Goa merger into Maharashtra, we get goosebumps. Goa’s unique identity would have been completely erased. Political representation would have been negligible, with Goa maybe becoming one peripheral district of Maharashtra. Present politicians should be thankful for the Opinion Poll, because today 40 politicians have a say in Goan political administration in shaping Goa’s future. Even persons who supported the merger then now take back their words when we speak at a personal level.

What lessons from that period do you think today’s generation should remember?

Unity, irrespective of religion, caste and self-benefit. The future of the Goan generation has already become very challenging. Goans are becoming a minority in their own state. Be united, be a real Goan, and protect Goa’s identity. All languages need to be spoken, protected and respected, but the mother tongue in its own state has to be given the highest regard. History tells us that despite Marathi-speaking political pressures, Goans preserved their identity for future generations. Every Goan has to be grateful and appreciate the activists who played a significant role in saving Goa. Knowledge of Goa’s history is very important for a Goan to properly understand their own identity. I request that all students should read the original history to get the right perspective. Parents and elders should guide their children about the history of Goa, and our young Goans will learn and appreciate the mindset and sacrifices of the Goans who contributed and worked for the existence of Goa.

Which leaders or campaigners stood out to you at the time, and why?

Everyone’s opinions of leaders and campaigners, for and against, were respected. Leaders such as Uday Bhembre, Ulhas Buyao, Chandrakant Keni, Purshottam Kakodkar, Shankar Bhandari, Noorani, Janardhan Phaldesai, Ravindra Kelekar and many more were at the forefront in mobilising Goans to support keeping Goa separate. All leaders and activists did not demand anything from the public. They presented the facts of the Goa–Maharashtra merger. We, as youth, helped them out. Nobody imposed any work on us. We worked dedicatedly as our thoughts were supported by the leaders.

How did the media — local newspapers and radio — cover the poll and influence people’s views?

Gomantak and Rashtramat were the key newspapers that actively shaped public opinion on the proposed merger with Maharashtra. Gomantak, a Marathi newspaper financed by Chowgule, reached Goans supporting the merger. To counter this and present the opinion of saving Goa, Chandrakant Keni, Uday Bhembre, Aravind Bhatikar, Garse and Timblo, to mention a few, were instrumental in publishing Rashtramat in Marathi to convey anti-merger thoughts and the Goa-saving attitude of Goans. Bhembre’s political column ‘Brahmastra’ in Rashtramat gained prominence and was influential in convincing Goans to vote against the merger, playing a significant role in the Opinion Poll’s outcome. People woke up in the morning only to read newspapers as Goan identity was at stake. Rashtramat was often read collectively and circulated among people until the next edition was released. Besides this there were many other papers.

How did ordinary Goans — villagers, youth and women — react to the campaigns?

The majority of people spoke Konkani, while Marathi was mainly used for religious functions. People stood their ground. Even people using Marathi understood the importance of Goan identity, while the Goan Catholic community also strongly supported the anti-merger movement.

Your thoughts as Goa marks six decades since the Opinion Poll.

The 60th anniversary of ‘Goans’ Identity Day’ or ‘Goencho Osmitai Dis’ has to be acknowledged by all Goans. The Goa government should have an annual celebration where the actual history of the Opinion Poll is known and appreciated by the people. Opinion Poll history should be included in the state history curriculum. This great event in Goa’s history should be proudly celebrated by the government, as it defines Goa’s identity and unity, which needs to be preserved by every Goan today.

Snippets

Soro lagta boro?

Liquor was banned in Maharashtra, which, unlike Goa, had prohibition. This became a bone of contention. To counter the ‘soro’, Maharashtra chief minister Vasantrao Naik announced in the legislative assembly that his government would not extend prohibition to Goa.

Marathi teachers’ support

Support for anti-merger came from unexpected quarters. To run the private Marathi schools that came up during the Portuguese rule, hundreds of teachers had come from Maharashtra, especially to the hinterland areas. After Liberation, they were absorbed into government service under the central government pay scale. Salaries for teachers in Maharashtra were much lower than the central government scale. As they wanted to protect themselves from possible transfer and a good pay scale, they secretly campaigned in their respective localities endorsing the anti-merger campaign.

Contentions

Among the arguments of the pro-merger camp were: besides the historical background of Maharashtra kings ruling Goa, it was argued that Marathi had deep roots in Goan society, from education and culture to literature and even religious rituals. The anti-merger camp, especially Rashtramat, said that the merger was an expansionist action by Maharashtra. They insisted that Goa had a distinct culture, unique from Maharashtra, and that Konkani was an independent language. They said that Goans adopted Marathi for education only because Konkani was suppressed in Goa during Portuguese rule, while it was able to flourish in the neighbouring state.

Material came from Maha

In the campaign that Bandodkar led for the Flower, much of the publicity material, as well as speakers, were ‘imported’ from Maharashtra. The Maharashtra Vilinkaran Samiti took the initiative to constitute an all-party Goa Merger Committee consisting of Congress, Praja Samajwadi Party (PSP), the communist parties, Jana Sangh, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and even trade unions like the Congress-led INTUC and Workers Union of India.

Volunteers too…

More than 100 volunteers came from Maharashtra for the pro-merger campaign. But the most powerful orators, such as Acharya Atre, Jayantrao Tilak, Shirubhau Limaye, S M Joshi, etc, didn’t attend. Congress leader and Rajya Sabha MP Mohan Dharia coordinated the campaign from behind the scenes. Socialist leaders such as Barrister Nath Pai, MP from Rajapur, addressed the meetings.

Congress incognito

The Goa Congress camp was not seen in public. Since the party was vertically divided over the issue in Maharashtra and Goa, as well as at the Centre, party president K Kamaraj imposed a ban on public participation in the Opinion Poll campaign and told party leaders to ‘play neutral’. Congressmen in Goa worked only at the cadre level.

Outside Goa voters

On the forefront to get outside Goans enrolled as voters was the UGP. Dr Jack de Sequeira left no stone unturned to achieve the demand, as he and his party led delegations to Delhi and Mumbai to ensure that they got voting rights.

Calm before storm

Sunday, January 15, witnessed silence before the storm. No one knew which way the wind was blowing. The campaign had stopped at 5 pm the previous day. The ‘outside’ Goans landed in Goa, many of them on January 16 itself, by air, rail and the most popular means of travel then, by ship. In fact, two ships arrived from Bombay—Champavati and Konkan Sevak. Some Goans flew in from Delhi.

3-day counting

Compared to the voter turnout in the first Assembly election held in 1963, the Opinion Poll evoked a huge response from eligible Goan voters, who came even from far and wide. While the polling was held on January 16, 1967, counting continued for three days, keeping Goans on tenterhooks. The counting centre was the Institute Menezes Braganza in Panaji. Flower was the

symbol of pro-merger and Two Leaves for anti-merger.

Corner meetings

In the corner meetings of the anti-merger camp, speakers asked questions to voters in MGP bastions such as: What do you prefer? Going all the way to Bombay (headquarters) to get your work done or going to Panaji? In Goa, MGP has already implemented the Land to the Tiller Act. So, why do we need to be in Maharashtra to get our land rights? And the final masterstroke, which may have worked wonders: Don’t you want our Bhau (Bandodkar) to continue as chief minister? In Maharashtra, at the most, he would become a token ‘minority minister’.

Polling beyond

scheduled time

People lined up at all the 442 election booths much before polling started at 8 am. It was conducted by the Election Commission of India. Many polling officers had to extend the deadline of 5 pm by 2–3 hours. In villages without electricity, Petromax lanterns had to be brought in for the polling process to be completed. Not just old people, but even patients and those bedridden were carried to the booth to cast their votes.

Aldona saw 97% polling

All across Goa, people showed enthusiasm. Eleven constituencies recorded polling percentages of nearly 90% or above. Aldona recorded the highest: 97%. Not a single constituency recorded below 74%.

Outside counting centre

From 9 am on January 17, the local station of All India Radio was continuously broadcasting a live commentary on the counting. Hundreds of people gathered outside the building to listen to the announcements and get updates of booth-wise results over the loudspeaker.

(Extracts from Sandesh Prabhudesai’s book — Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics)

Dayanand Bandodkar: The moderate mergerist?

History has to be fair and judge Goa’s first chief minister Dayanand Bandodkar from the standpoint of truth. In the book ‘Post-Colonial Politics in Goa Cabinet Government Union Territory to Statehood 1961-1994’ Dr A Freddy Fernandes writes that Bandodkar was not a ‘die hard Mergerist’. Fernandes has used the phrase ‘moderate mergerist’ to describe him and cites Goa Assembly debates and the passing of the bills on Merger and Marathi. Excerpts from the book.

It is very interesting to note how Dayanand Bandodkar’s change of heart and mind came about on virtually delaying and paying lip service to the Merger issue. Bandodkar’s conversion to a “go slow moderate mergerist” came after his transforming encounter with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in Bombay, in December 1963. He gradually veered away from the merger agenda, as he would be the master of the political destiny of his own state-Goa.

Changed stance

Pragmatic as he was, Bandodkar decided to avoid a confrontationist course and decided to “go slow” on merger. “We do not want to impose Merger on anybody,” he reiterated in an interview where he said that his party would not press the merger move for quite some time

This decision backfired as far as his leadership was concerned and resulted in a serious threat to his party and executive leadership. The first threat to Bandodkar’s party and executive leadership emerged from the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) MLAs Jaisingrao Rane and Gajanan Raikar. The duo threatened to resign on January 2, 1964, even before the first assembly session. Both MLAs claimed that Bandodkar’s decision was an outright betrayal of pro-merger votes. Bandodkar managed to successfully ward off the crises due to his influence with the PSP central leadership.

Bandodkar misled

It is also evident from the fact that going into the third election of 1972, Bandodkar espoused statehood for Goa, having overcome the blunder of merger. He also promoted the cause of Konkani as Official Language, along with Marathi going into the 1972 election.

It is also said that Bandodkar was misled by the Maharashtra lobby of politicians, which led him to believe that he would be made chief minister of Maharashtra, but when he realised that he was the master of the destiny of Goa, due to majority rule in the post liberation period, thereafter he only paid lip service to merger.

A reading of legislative assembly debates and history shows that most of the dissidence faced by Bandodkar during his three terms in office were because he did not move fast enough on merger. He even faced a no confidence motion.

‘Double speak’ strategy

To avoid similar threats to his leadership from now onwards, Bandodkar freely indulged in what I term as ‘double speak’ on the crucial agenda of merger of Goa with Maharashtra. In using ‘double speak’ I refer to Bandodkar’s strategy of pleasing both mergerist and anti-mergerists, by making pro-merger and pro-Goa statement. This remained Bandodkar’s strategy of survival throughout, till the 1972 elections when he put statehood for Goa on his party’s election manifesto, after all rebellion within his party was quelled and he was the undisputed leader of the party.